Borno man who fought in America’s Civil War in the 1860s

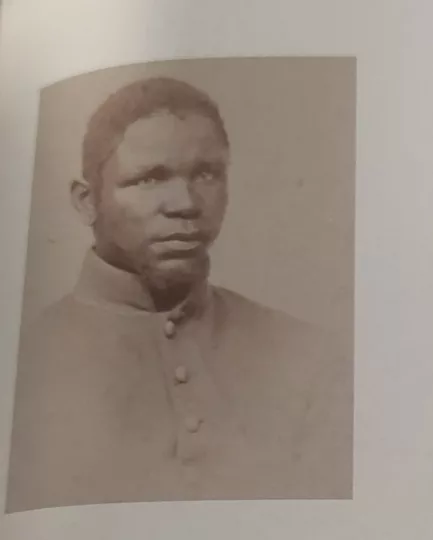

Nicholas Said

Published By: Kazeem Ugbodaga

By Farooq A. Kperogi

In the spirit of America’s Black History Month, which is celebrated every February, I am continuing my tradition of writing columns that focus on the unique experiences, trials, and triumphs of Black Americans.

My focus this week is on an intriguing, superbly brilliant, impressively polyglottic, but surprisingly unknown Borno man by the name of Nicholas Said, who migrated to the United States a little over a year before the American Civil War started on April 12, 1861, in which he fought on the side of Union forces.

I first encountered Said’s story sometime last year by chance while watching a documentary about the early Muslim presence in America. During the film, a Black American Muslim woman mentioned Nicholas Said, whom she said traced his natal roots to a part of what is today Nigeria.

I was struck by two things: the onomastic oddity of his name (what Muslim man from what is now Nigeria would bear such an incongruous appellative identifier as “Nicholas Said” in the 1860s?) and the absence of the man in the accounts of early Muslim Americans, a field with which I am fairly familiar.

My curiosity led me to abandon the documentary midway in search of the man. It turned out that he wrote his own autobiography in 1873, titled The Autobiography of Nicholas Said: A Native of Bornou, Eastern Soudan, Central Africa. I immediately placed an order for it on Amazon.

I also bought Dean Calbreath’s irresistibly absorbing 2023 book on Said, titled The Sergeant: The Incredible Life of Nicholas Said: Son of an African General, Slave of the Ottomans, Free Man Under the Tsars, Hero of the Union Army, which I read with the kind of hunger that turns pages into a feast, each chapter a savoury bite of history too rich to put down.

Said was born Mohammed Ali ben Said around 1836 in Kuka (now called Kukawa) to a Kanuri father and a Mandara-Margi mother. He became “Nicholas” much later in his life when he became a servant to a Russian prince, who converted him to Christianity. I’ll come back to this.

Kukawa, Said’s hometown, was the capital of the Borno Empire and the immediate successor to the previous, storied 340-year-old capital called Ngazargamu.

By the 1840s, during Said’s boyhood, European travellers who visited Borno recorded that Kukawa had a population of around 100,000. “By comparison, in 1840, only 11 cities in the United States had more than 40,000 residents,” writes Dean Calbreath.

He was the 13th of his mother’s 19 children. His father, more popularly known by the moniker Barka Gana (“little blessing”)—a name bestowed upon him by Sheikh Mohammed el-Kanemi, who trained him in Arabic and Quranic memorisation in Ngala from ages 9 to 12—was a fierce, furious, and far-famed fighter in Borno’s army. His ruthless conquest of enemies earned him the chilling nickname Malak al-Mawt, Arabic for “Angel of Death.”

He was Borno’s chief Kachala, what we would call today the Chief of Army Staff, during the reigns of Sheikh Mohammed al-Amin ibn al-Kanemi and Sheikh Umar, al-Kanemi’s son.

Decades before Nicholas Said migrated to the United States (and, before that, to Europe), his father’s name and exploits had already reached both continents through an 1826 book titled Narrative of Travels and Discoveries in Northern and Central Africa: In the Years 1822, 1823, and 1824. Authored by three European travellers—Dixon Denham, Hugh Clapperton, and Walter Oudney—the book documented their time in Borno and the events they witnessed there.

One particularly poignant encounter they witnessed was the resolution of a personal conflict between Said’s father, Barka Gana, and the king of Borno, Sheikh al-Kanemi.

Following Barka Gana’s decisive military victory, al-Kanemi, delighted with his general’s success, presented him with a beautiful horse as a token of appreciation.

However, al-Kanemi remembered that he had promised the same horse to someone else and thus requested Barka Gana to return it. Enraged by al-Kanemi’s act, Barka Gana, who had cherished the gift, not only returned the horse but also every other horse al-Kanemi had ever given him.

This act of defiance infuriated al-Kanemi so much that he ordered that Barka Gana be stripped naked in public, denuded of his position, and sold as a slave abroad. Barka Gana apologised for his arrogance, accepted his fate, but pleaded that his wives and children be spared.

When he returned to the palace the following day to be sold into slavery, al-Kanemi fixed his gaze on him and couldn’t hold back tears. The king cried publicly and forgave his general.

The account of this incident—and of Barka Gana’s military exploits, devotion to Islam, fierce loyalty to the Shehu, etc.—by European travellers who witnessed it firsthand and wrote about it was “so popular it was translated into French, German, Spanish, Italian, Dutch, and Russian, and over the coming decades, poets, clergymen, scientists, and politicians reshaped its stories to suit their purposes,” according to Calbreath.

In London, scientists held Barka Gana as evidence that “Africans had the same brainpower as Europeans.”

In the American South, where Black enslavement and notions of Black subhumanity were mainstream, abolitionists used the story of al-Kanemi’s tear-jerking restraint from inflicting punishment on Barka Gana to illustrate the point that “we Americans, particularly of the South, may take a useful lesson from these sable sons of Africa and learn to emulate their Christian feelings of ‘mercy’ and ‘moderation’ before we go to civilise them.”

In fact, Barka Gana’s story made it to the U.S. Congress. House of Representatives member Charles Miner from the state of Pennsylvania, who was an abolitionist, said in Congress that Barka Gana’s dexterous warfare tactics should serve as an inspiration for the U.S. Army to reverse its ban against Black people serving in the military.

“The African race makes excellent soldiers,” Miner said. “They are admirably adapted for military service.”

By a stroke of historical happenstance, decades later, Barka Gana’s son, Nicholas Said, would serve as a sergeant in the U.S. Army and fight in the American Civil War to end the enslavement of Black people.

But, first, how did he get to America? When he was about 9 or 10 years old during Maulud, he and his friends went hunting in the abandoned and uninhabited town of Lari—against the advice of his mother (his father had died by this time)—who warned him that he would be “captured by the Kidnapping Kindils, a wandering tribe of the desert, who were constantly prowling through the country in search of anything of value they might lay their hands on.”

Kindil was the name the Kanuri people used for the Tuareg (i.e., Buzu) people.

His mother’s prediction materialised: he and his friends were kidnapped. For months, their abductors forced them to march thousands of miles through the Sahara Desert in chains until they reached what is now Libya, where they were sold as slaves.

The wealthy man who bought him later recognised that he was the son of the world-famous Barka Gana and offered to free him. But Said was “unwilling to recross the inhospitable Sahara” and chose to remain a slave, although he was treated much better than other slaves.

*This will be continued next week.